This edition of the Mexico Water Report has a mixture of private and public sector articles. The first article deals with the problems that foreign companies are facing when trying to participate in water government procurement bids and the reality that many government bids are no longer viable for US companies under newly published rules and despite the existence of NAFTA – and how we can do something to change these regulations.

The second article deals with channel realities for selling to the water sector in Mexico. Our next edition will have an article that completes our analysis on this all important theme. The next two articles deal with private sector analysis.

The third article continues our analysis of economic segments that require water equipment - their current dynamic and water problems and opportunities – reviewing the dairy, textile/clothing and metal working/automotive sectors.

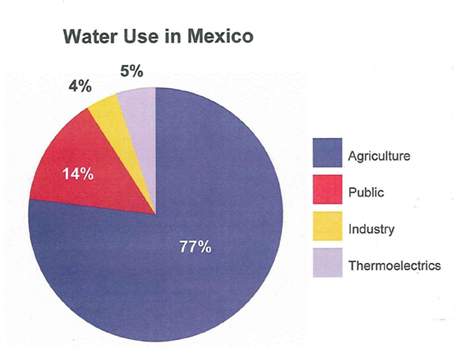

The fourth article provides an overview of water in agriculture in Mexico – where almost 80% of national waters are destine (4th highest in the world) but where less than 2% of water revenue is based. The final article describes the water infrastructure and opportunities that exist in the all important Mexican Federal District/Mexico City area.

In this edition we will address:

Upcoming Visits by the Mexico Trade Office Director

Vince Lencioni, Director of Wisconsin's Trade Office in

Mexico,

will be in California in March, Washington, DC and Pennsylvania in

April and June, and the upper Midwest in May. If any

companies would like to meet with the director during these trips,

please see the below visit details and contact us so that we can try to

schedule a visit.

March: 2030 Mexico Water Program Announcement and

Analysis – In March, the Mexican federal

government will give out details concerning the proposed 2030 Water

Program. LGA Consulting will provide a full analysis of these

concrete points related to what Mexico plans to do regarding water

technology and infrastructure during the next 20 years.

Please let us know if you would like to receive this

analysis.

April 19-21: Waste Water Equipment Manufacturers

Association (WWEMA) Annual Convention in Washington, DC - The director will be participating and presenting about

the water sector in Mexico, and available to meet with

businesspeople.

May 9-13: Annual Visit to Wisconsin - The director's of Wisconsin's four international trade offices

(Mexico, Canada, Brazil, and China) will be visiting various locations

in Wisconsin to speak on developments and opportunities in their

markets as well as have one-on-one appointments with Wisconsin

businesses seeking to expand their export sales.

June 12-16: AWWA ACE11 Event in Washington, DC - The director will be attending the show and available to meet with

businesspeople.

When the International economic crisis hit Mexico in late 2008, Conagua

(Mexican Water Commission) established that its funding of public

sector water projects would continue forward without delays.

And, while one can argue that many projects did continue forward,

especially in 2009, projects in 2010 were dramatically affected by

budget, political/electoral, and typical Mexican bid

bureaucracy. It appears now that many projects delayed in

2010 will likely come back on line in 2011. However,

Wisconsin's Trade Office in Mexico warns that for foreign companies, it

sees only serious concerns and larger problems and deceptions affecting

their participation, or ability to participate, in Mexican public

sector projects now and in the foreseeable future.

This article will explain the blurring that has taken place between

National and International bids in general and especially with new and

stricter national content regulations, as well as how ineffective NAFTA

has been in protecting US and Canadian companies from this new Mexican

protectionism. It will also discuss how and why foreign

companies and companies trying to provide non-Mexican made product

should be concerned about remaining viable in the Mexican public water

sector.

Evolution of National Content Regulations in

Mexican Government Procurement

In November of 1994, six months after NAFTA went into affect, Mexico

established a rule that 50% of the contracts of federal, state, and

municipal governments should be with small or medium Mexican companies,

an interesting, progressive measure that for the most part was not

enforced or enforceable. Ironically, although the NAFTA

chapter on government procurement was supposed to create opportunities

for US and Canadian companies and protect at least them from

protectionist procurement measures in Mexico, said rule served as a

precursor for much more protectionist measures in this area that would

come from the Mexican federal government in November of 2000 and even

more strongly in October of 2010.

In November of 2000, Mexico published its first Rules for the Determination and Accreditation of the Amount of National Content for Federal Government Procurement. In these rules, the Mexican government established that all federal government procurement goods purchases needed to have at least 50% national content. While procurement laws established that public works contracts could only be bid on by Mexican based companies, said contracts did not have any national content requirements. While said regulations allowed Mexican federal dependencies to establish national content minimums, this was something that was rarely done.

While these new national content requirements for the purchase of goods (but not on public works) now existed, said regulation (a) was not implemented with a heavy hand at the federal level, (b) state and municipal procurement officials virtually ignored these stipulations, and (c) federal officials looked the other way at these state and municipal transgressions. As a result, despite the creation of these 2000 Rules foreign companies could find a viable way to do business in the Mexican procurement system.

In October of 2010, the 2000 Rules were modified to make it even more difficult for foreign companies to participate in the great majority of government bids at the federal, state, and municipal levels. And more importantly, the implementation of these rules appears to be real and consistent this time, unlike in the case of past procurement and national content laws and regulations. Prior to the October 2010 National Content rules changes, the opportunities for foreign companies could be understood to be generally viable and even somewhat ample. If a foreign company had a Mexican subsidiary or sold its products through a Mexican intermediary, then they could participate freely in all bids, including national bids. However, the new 2010 regulation and its heightened implementation dramatically affected this viability. With the extension of national content to public works and the more strict enforcement of the national content regulations, foreign companies are effectively excluded from being able to participate in national bids even via a Mexican intermediary because said bids now require 55% national content, and they will require at least 65% national content in less than 18 months (in July 2012). And, the 2010 regulations are being interpreted so that even international bids are subject to national content requirements when Mexican products and technology can meet bid requirements.

Analysis of the Changes Resulting from the October

2010 Regulations

The most important change for the water sector brought about by the

October 2010 National Content rule changes was related to the

establishment that all municipalities and states that used any federal

funding (80-90% of these cases or more) would have to abide by these

new regulations as well. This change at the municipal level

is something new and particularly damaging for foreign companies in the

water sector since more than 95% of Mexican bids in this sector are

municipally procured, and since municipal and state government bodies

are exempt from NAFTA protection. It is interesting to note

that while the Mexican federal government insists on the exclusion of

municipal and state procurement from NAFTA protection, arguing that

said entities are not truly federal and therefore exempt, it

nonetheless conveniently uses municipal dependence on federal funding

to insist that said entities have to comply with these federal

regulations. This makes these entities de facto federal

bodies from a national regulatory perspective but evidently and

conveniently not from a NAFTA perspective. Is this a

legitimate legal loop hole or a classic example of having your cake and

being able to eat it – we see it as the later.

Another negative has emerged from this heightened enforcement and

percentage increases in national content rules. Foreign

companies and/or their Mexican intermediaries or partners, are being

forced to decide between being excluded from the Mexican government

procurement system altogether or lying and stating that their products

meet national content minimums and bribing local officials to look the

other way, hoping that federal oversight will not catch their

digression. Wisconsin's Trade Office in Mexico is already

aware of a few cases of this type of behavior by foreign

companies. This is not only inappropriate and illegal in

Mexico, it also goes against US export practice laws that the US

federal government promotes and enforces, thus providing US companies

with another barrier to remaining viable in its second most important

export market, a market where NAFTA was supposed to mean the

elimination of old trade barriers and not the creation of new

ones. We fear that too many local Mexican water procurement

officials will become more aggressive in the future at using this

national content rule as a tool for corruption, being able to function

even more effectively and efficiently with it as gate keepers approving

or eliminating bids at the beginning of the process using this legal

“ruler” more adeptly than previous more onerous and

questionable instruments.

It is important to mention that foreign manufacturers and Mexican

intermediaries who sell foreign products into the Mexican public water

sector are now beginning to see the implementation of these changes,

that is, a commitment by the Mexican federal government to enforce

these regulations and subsequently a new adherence by municipal and

state governments to these regulations. Some

companies who sell components to Mexican integrators, where a large

part of a public work is labor or construction, seem to be less

affected so far by these regulations. However, in 18 months

when the percentage of minimum national content is 65%, this could and

probably will change. And, it is important to clarify that

these percentages are MINIMUM requirements and that foreign companies

and Mexican distributors of their products are saying that they are now

routinely running into bids where the percentages are above 65% and has

high as 100%. For a company trying to sell product via a

Mexican distributor to the Mexican government in a bid only for that

product, virtually any national content requirement, as is the case in

Mexico, will serve as an effective way to exclude these products from

the market.

Analysis of NAFTA Government Procurement Provisions

Above we mention that NAFTA Chapter 10 Government Procurement does not

seem to offer US and Canadian companies adequate protection from

Mexican protectionist government procurement policies. When one reads

the key articles in this Chapter, it is hard to imagine how US and

Canadian companies are not protected from these types of

actions.

Article 1003 – National Treatment and Non-Discrimination

Even US federal government officials responsible for NAFTA issues

confirm that said articles do not protect US and Canadian companies

from unjust Mexico government procurement procedures, specifically

prohibiting US companies to bid directly without Mexican intermediaries

and prohibiting Mexican government entities from using restrictive

national content regulations to exclude US companies from the

sector.

Likewise, Article 1024 (Further Negotiations), referenced extensively

above in Article 1001, which discusses the initiation of negotiations

for improvements in Chapter coverage to include local/state entities

under Chapter 10 provisions, has NEVER taken place even though said

article mandated that negotiations were supposed to start between the

three parties no later than 1998 - 12 years of no activity on the

issue.

In the case of international bids, it is now illegal, not to mention completely impractical as the system exists today, for a foreign company to bid on any international bids without a Mexican corporation, partner or intermediary as the formal bidder. As a result, any foreign company hoping to employ a rep or agent for this purpose can no longer do so. If NAFTA was supposed to help in this area, it absolutely has had no effect except to deceive US companies into believing that somehow they were better protected from these types of issues and problems after 1994 than before 1994.

Another problem lies with the Mexican government procurement system. Said system is structured so that effectively three types of bids are permitted: (a) national bids in which only Mexican-based companies can participate, (b) international bids where companies from countries with free trade agreements (like NAFTA) with Mexico can participate, and (c) open international bids where companies from any foreign country can participate. However, foreign companies cannot participate in any of these bids without a Mexican entity, despite what NAFTA seems to establish. One might argue that foreign companies should be content to be able to participate in the international bids and agree to set up Mexican corporations to participate in national bids or simply allow Mexican companies to have these national bids that one might assume are of lower value and probably fewer in number than the international bids. However, Wisconsin's Trade Office in Mexico analyzed all public sector water bids between July 2009 and June 2010, and found that during that year period, only 2.28% of all such bids were international in nature. In speaking with Mexican water government officials involved in procurement bids, it appears that this is a trend that will continue and by no means an exception.

These Chapter 10 articles have been ignored or Mexican officials have found ways to change their meaning and circumvent their enforcement so that Chapter 10 is completely ineffective and out of step with if not contradictory to the spirit and purposes behind the inclusion of a government procurement chapter in NAFTA. As a result, one has to ask, does Chapter 10 have any merit or help protect US and Canadian companies in any way from Mexican government protectionism in government procurement – we have to conclude that it does not.

U.S. and Canadian Procurement Laws vs. Mexican

Procurement Laws

The above information in this article demonstrates that Mexican

government procurement laws and regulations are clearly protectionist

in general and even towards US and Canadian products, something clearly

not in the general spirit of NAFTA nor the spirit or evidently the

reading of Chapter 10. An easy but incorrect assumption might

be made that the US and Canadian government procurement laws and

regulations are probably just as protectionist as those in

Mexico. While Wisconsin's Trade Office in Mexico has not

studied this issue exhaustively, from conversations with US federal

government officials and from some investigation of some applicable

regulations, it seems that the US does not treat NAFTA partners, nor

for that matter countries with which it does not have free trade

agreements, in the same negative way that Mexico does. The US

does offer protection for some metal/steel producers in government

procurement bids, but said protection is clearly temporary in

nature. These US measures neither apply to all products that

are procured by the federal government nor are written into the law as

something intended to be permanent, as is the case with the Mexican

National Content Regulations published in October of 2010.

It is important to mention that all of Canada´s provinces and

almost 2/3 of US states have ratified the GATT Agreement on Government

Procurement, which establishes that these entities cannot discriminate

against foreign products the way that the Mexican federal government is

currently doing. And, to our knowledge, not a single Mexican

state has made any effort to look into the ratification of this GATT

Agreement. One has to ask why this is so and why the Canadian

provinces and 2/3 of the US states should adhere to these more

stringent, non-protectionist GATT policies if their NAFTA partner

counterparts have expressed no interest or willingness to pursue

similar actions.

Conclusion

Many U.S. and Canadian manufacturers who were expecting government

procurement opportunities to come from NAFTA and the supposedly more

liberal, open Mexican economy have to be feeling deceived.

One can easily argue that Mexican laws and NAFTA have not only not

created procurement opportunities, they have restricted if not

eliminated most opportunities that existed before NAFTA. This

claim is serious because It comes with three very negative

implications: (1) NAFTA is almost useless and even detrimental for

government procurement opportunities in Mexico, (2) in the area of

government procurement there exists a serious lack of commitment by

Mexico to trade relations with its most important trade partners, and

(3) Mexico's government procurement policies demonstrate serious

contradictions in the loud and proud stance of the Mexican federal

government that if a country signs a free trade agreement with Mexico,

its market will be opened to the products of the companies from these

nations.

Shouldn´t Mexico exclude countries that have signed free trade agreements with Mexico, especially the U.S. and Canada, from these blatantly protectionist measures? And, if it does not see the reasoning and prudence of doing so, shouldn´t the U.S. and Canadian federal governments be more vocal in public and more active in bilateral and trilateral negotiations with Mexican officials about these concerns. In the next edition of the Quarterly, we are going to discuss options for how U.S. and Canadian water-focused companies and their respective associations can work together with their respective governments to get these measures modified if not repealed. If any foreign companies or Mexican intermediaries would like to interface with Wisconsin's Trade Office in Mexico to discuss these issues and future lobbying efforts, please do not hesitate to contact us.

In our last edition, we described the five most important sectors in terms of discharge concerns, all of which had some kind of special Conagua sectoral program to regulate their discharges, above and beyond standard wastewater discharge regulations. In this edition, we are analyzing the following three, large and important manufacturing sectors, providing a feel for their size, current dynamic, and details about their environmental problems and related opportunities: A. Dairy Industry, B. Textile and Clothing Industries, and C. Metalworking and Automotive Industries.

A. DAIRY INDUSTRY

Size & Current Dynamic

Mexico consumes about 15 billion liters of milk annually but only

produces 10.8 billion liters domestically. One important reason

why Mexico has to rely so heavily on milk imports is water deficit

issues. To produce one liter of milk in Mexico, 300 liters of

water are required. Many of the leading production sites are in

some of the driest areas of Mexico. With a growing urban

population, milk demand in Mexico is growing three times faster than

production.

Mexico currently produces almost 75% of the milk demanded by its

domestic market. Imports represent about 40% of all processed final and

intermediary dairy products, both because of price and because many

local producers fail to meet quality standards. The US provides

two-thirds of all milk and milk product imports with 15% coming from

New Zealand and the other 20% from Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and

Australia. Although Mexico has historically relied on imports of

milk powder, in the last 10 years it has been able to become more

reliant on local product, thanks to the development and increased

presence of Alpura and Lala.

Mexico ranks 8th in the world in terms of milk and dairy product

production with 11.1 million tons of milk and milk products

(2009). The industry is divided between 20 large, highly

technical companies with approximately 70% of the production. The

two largest companies, Lala and Alpura, control approximately half of

that segment. An estimated 259,000 small manufacturing operations

account for the remaining 30%. The ability to tackle water issues

is significantly different depending upon whether a firm is one of the

large or small producers.

Lala has doubled its size during the last three years and has become the leading dairy company in all of Latin America. It also has an important presence in the United States. Between its production and purchases, market experts estimate that it controls 60% of the liquid milk market and 45% of the milk products market. The company’s headquarters is in Torreon, at the center of the Lagunera Region which has become the hub of sophisticated Mexican dairying. It has 11 major operation centers located throughout the country and annual revenue of over US$5 billion, making it the 25th largest company in Mexico.

The Alpura Group is the second largest dairy company in Mexico with over 82,000 cows in 160 stables that produce more than 2 million liters of milk per day, approximately 10% of all of the milk produced in Mexico. It has 15 distribution centers with 60 distributors located throughout the country. The Alpura Group consists of 11 companies specialized in every stage of milk production and milk product development and sales. Alpura is headquartered in the State of Mexico, near Mexico City, and has production facilities in eight states in the northern and central parts of the country.

Despite the success of Lala and Alpura in the last 10 years, most of the other dairy companies have faced serious threats from increased imports, increased costs, and government imposed price controls. Mexican milk producers must sell their product at low government-set prices which dramatically affects the profitability of the small and medium-sized producers. These smaller operations insist they cannot afford to modernize unless milk prices are allowed to increase. As a result of these pressures, and the lack of adequate financial supports, many small producers have closed their stables for good.

While Lala and Alpura are better equipped to provide additional domestic production to meet this demand, half of their milk comes from small and medium producers. As a result, even before the arrival of the current international economic crisis, these low milk prices affected the abilities of small, medium, and large producers/processers to meet the growing domestic demand.

Opportunities

There is a general feeling that the residual products from dairy

production processes are not harmful to the environment. However,

while dairy process waste is mainly organic and is not toxic, its

increased concentration in Mexican ecosystems has become a real concern

and caused an important environmental disequilibrium. This is

especially significant in rivers located near large milk production

plants. Aside from concerns about waste volumes, the organic fats

and proteins waste products, independent of concentrations, require

more and better treatment. Corporate culture and concern about

public complaints together with increased Conagua enforcement measures

have made milk producers, large and small, take notice and acquire

appropriate equipment to provide solutions to these problems.

The production process of the largest Mexican dairy plants is

increasingly using new technology, at least in part to better handle

the disposal and treatment of organic waste. Smaller companies

are not so fortunate in light of the considerable expense and important

investment required to adequately modernize and maintain some of these

treatment solution systems. Mexican companies recognize the

prudence of meeting Mexican wastewater standards. As a result, we

see the demand for treatment solutions in the dairy sector growing as

the sector grows. Large companies will meet requirements because

they are in the spotlight and have the ability to pay for these

solutions, and medium and small companies due to increased vigilance by

local water and Conagua officials.

A large number of small producers are struggling to remain viable and

lack the capital to implement anything other than rudimentary

processes. More stringent regulations or more comprehensive

enforcement would benefit the Mexican consumer, but its cost would

likely cripple the small- and medium-sized milk producers.

B. TEXTILE & CLOTHING INDUSTRIES

Size & Current Dynamic

The textile and clothing sector is very important in Mexico, generating

a fifth of the country’s manufacturing jobs and contributing 8% to

manufacturing GDP. The sector generates annual revenues of over

US$9 billion. Thanks to NAFTA, Mexico has become the United

States’ top supplier of apparel and the second most important supplier

for textiles, just behind Canada.

Illegal imports of counterfeit consumer clothing is having an adverse

effect upon Mexico’s domestic producers. Domestic production

methods remain outdated and inefficient and most companies feel they

cannot afford to invest in better manufacturing processes and related

equipment. Despite the threat from Asian, and to some extent,

Caribbean competitors, large transnational firms are able to succeed in

Mexico based on foreign financing, modern technology, and an emphasis

on production for export to the United States. To increase the

competitiveness in the Mexican clothing and textile industries,

companies need to capitalize and modernize their facilities.

While the sector absolutely requires more capital, credit, and

financing, increased combat against smuggling is also important.

Opportunities

The textile industry is a large water polluter due to the use of dyes.

One of the alternatives to avoid this type of pollution is the use of

natural absorbents and synthetic pollution removal solutions like

chromium, arsenic, inorganic compounds and fluoride, among others. The

public is alarmed when dyes discharged into municipal sewer and

rainwater drainage systems change the color of rivers and

streams. Less visibly, dyes severely affect water in lakes and

rivers because the different dye contaminants prevent the passage of

sunlight which is essential to photosynthesis in the affected

watersheds. Decreased photosynthesis reduces the amount of

dissolved oxygen in the water available to fish and other water

life. This causes a kind of methanogenic fermentation. Synthetic

absorbents are used to both reduce industry pollution and discharge

toxicity, and modify the artificial color of the water.

The textile industry is regulated by standards that deal with the

discharge and treatment of waste and wastewater. In the past, the

two applicable standards, NOM 001 for discharges into municipal sewer

systems, and NOM 002 for discharges into federal bodies of water, did

not include parameters for certain contaminants. Many of the

contaminants that the EPA regulates in the United States are not

mentioned in Mexican regulations. Mexico also lacks the manpower

and will for the enforcement of these general wastewater

standards. However, in light of these deficiencies, Conagua

officials are carrying out specialized monitoring in areas where there

is a concentration of clothing and textile production to ensure that

these companies, especially large- and medium-sized companies, meet

environmental regulations by properly treating their waste before it

enters municipal systems and federal water bodies.

Like the diary industry, one of the main problems is the difficulty in

identifying and monitoring small company discharges that go directly

into sewer systems. While large companies will produce larger

volumes of discharge, their more modernized process equipment

frequently means that the level of contaminants in their discharges

will be much lower and generally less toxic than those of smaller

producers who create much less discharge but with much higher

contaminant levels. Wisconsin’s Mexico Trade Office sees

opportunities in this sector in both areas, especially since dye

contaminants and related water discoloration can be readily identified

by the public and it appears that the Mexican public is increasing

complaints to Conagua officials who have the authority to fine and even

close plants for this type of non-compliance.

C. METALWORKING/AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRIES

Size & Current Dynamic

There are about 24,000 companies that are directly involved with the

metalworking industries in Mexico. The metallurgical industry in

Mexico produces and generates economic benefit equal to $21 billion USD

country-wide. In the last few years, the lack of sophistication and

technological level and in general the lack of equipment have led

companies to seek partnerships that will bring them the technology

and investment they require. This sector is responsible for 1

million jobs representing 13.5% of the country's manufacturing value,

contributing nearly 3% to the Mexican GDP.

The automotive sector is key to the metallurgical industry in Mexico,

responsible for 17.3% of the manufacturing GDP with more than 20

assembly factories , located in 12 different states. The

auto parts industry has plants in 26 of the 31 Mexican states and

counts with a network of more than 1400 dealers in urban areas across

the country. About one million jobs depend on the automotive and

auto parts sectors in the country, apart from the 1 million described

above for metalworking industries. The greatest challenge for

automotive companies is to reduce costs and processes while continuing

to meet high quality requirements, challenges that have somewhat

negatively affected Tier 1 and Tier 2 contracts with OEM companies in

the sector during the last few years.

Year end 2010 figures for the automotive industry demonstrate very

healthy relative growth compared to the stagnant 2009. Year end

production (2,260,776 vehicles) was up 50 % over 2009 figures with over

750,000 more units built in 2010. Also, exports were up 50% and

domestic sales were up 8.7% for the year, and up 14% during the month

of December 2010. However, the 2010 increase vs. 2008 figures was

more mixed. Compared to 2008, Mexico produced 12% more vehicles

while exporting 3% less and selling almost 50% more into the domestic

market.

The contraction of the exportation of auto parts and Tier 1 and Tier 2

segments during the last few years was sharper than the fall off of

sales to the domestic market. Nonetheless, and although domestic

sales are growing, the rebuilding of the vehicular base now that

recovery is on the way is still a year or two away. As for the

current dynamic in these sectors, while 2010 was better than 2009 and

2011 will be better than 2010, recovery in the sector is not expected

until 2012 when it is hoped that production levels will return to 2008

(pre-crisis) levels.

Opportunities

The metallurgical industry, in addition to this important production

contribution, generates tones of hazardous and non-hazardous waste.

This includes iron chips from grinding and drilling operations which

usually are impregnated with oil and lubricant soluble. These are often

sold to foundries or deposited in municipal waste centers. Iron waste

not only serves as an important source of raw materials for

metallurgical industry, it is also used as a reducing agent in the

treatment of different pollutants.

In terms of water pollution, the automotive industry has had serious historical and some current problems dealing with compliance issues. Large OEM companies as well as Tier 1, Tier 2, and auto parts manufacturers have problems with the inappropriate use of and care for toxic chemicals in the manufacturing process. Automotive companiese, especially small and medium non-OEM companies, too often discharge metal waste byproducts and chemicals without control, measurement or treatment, causing serious damages to aquifers and other water bodies.

It appears that the most serious discharge and contamination issues in this industry are more or less under control, especially with the larger metalworking and and OEM companies. Increased government monitoring of associated water supplies and environmentally responsible corporate cultures has led to rather consistent compliance with Mexican environmental regulations and, with regards to historic problems, the carrying out of cleaning and restoration efforts of contaminated aquifers by these large and important producers. However a lot of auto parts, “Tier 1” and “Tier 2” companies are not nearly as well regulated, compliant, or identifiable, and these companies too often discharge directly into municipal sewer and drainage systeme, and therefore federal water bodies, without any treatment.

Conclusions about Opportunities in these Sectors

Like in the case of several of the above mentioned sectors, there are

three distinct types of opportunities for environmental equipment sales

and solution providing. The first and most obvious is with the

larger manufacturers who often have corporate cultures or public images

related to the environment that they must preserve and they are

generally under the microscope of government authorities. The

good news is that they have the funds and impetus to find and implement

solutions. While many of these companies require on-going

assistance, many also already have systems in place.

The second is with small companies who have enormous needs but who are

short of funds, can´t get financing, do not have appropriate

corporate cultures and are difficult for the government to identify and

enforce. It takes a special, low-cost solution that allows for a

fairly quick return on investment for a company to find a niche with

these types of companies.

In the middle are medium-size companies, in the case of the automotive

sector many auto parts, “Tier 1” and “Tier 2” companies. These

companies have some of the funding but probably do not have adequate

financing to purchase the systems that larger companies can, but with

enforcement of NOM 001, NOM 002, and special sector program progressing

from larger to medium-size companies, these companies sooner than later

will be faced with the reality that they, like their larger

counterparts, will need to make similar environmental equipment

investments to remain compliant. Medium size companies, like

medium-sized cities, will be targets for compliance and environmental

investment in Mexico during the next ten to twenty years.

This article will review, as an introduction of sorts, the characteristics of the Mexican regions, by water and agricultural characteristics, to give the reader a perspective on Mexican water use and related national and regional goals and objectives to make the Mexican agriculture system more productive, efficient, and sustainable by means of better water management. Future editions will deal with each of these issues and other related issues in greater detail.

This article will specifically address the following agricultural-related water issues:

The geographical area dedicated to agriculture in Mexico is about 21 million hectares, which represents 10.5% of the total Mexican land surface. On average, Mexico harvests about 19.6 millions of hectares per year with 6.5 million under irrigation and 14.5 million dependent almost exclusively on seasonal rains. The crops grown in irrigated areas receive water from surface and/or groundwater supplies.

When comparing national land mass dedicated to agricultural activities, Mexico (10.5%) is not dramatically different from its trade partners nor those Latin American countries with similar or significant agricultural focuses:

However, none of these countries provides anywhere close to Mexico's 80% of total water supply for the agricultural sector:

There are several factors that contribute to the extensive use and

excessive waste of water by Mexican agriculture. The most obvious

causes are the low price of water for Mexican farmers and the lack of

accurate measurement of water consumption. Without adequate

metering technology and despite the lack of water in different regions

of the country, farmers only pay a very small part of their water cost,

paying a base rate that serves as a poor, low estimation of their

consumption.

There are several factors that contribute to the extensive use and

excessive waste of water by Mexican agriculture. The most obvious

causes are the low price of water for Mexican farmers and the lack of

accurate measurement of water consumption. Without adequate

metering technology and despite the lack of water in different regions

of the country, farmers only pay a very small part of their water cost,

paying a base rate that serves as a poor, low estimation of their

consumption.

There is another somewhat unique Mexican factor that leads to this misuse. The low volume assignations due to low levels of water in dams creates an interesting phenomena. Under this circumstance, when Mexican farmers irrigate their crops, they extend the irrigation time to ensure that their fields get an exaggerated amount of humidity in case water is not available at the later, programmed time.

A final factor is the need for modern irrigation methods and the training of Mexican farmers in irrigation processes which could and should be an important part of the solution for these problems. It is estimated that these efforts could impact the total amount of agricultural water loss by as much as 60-70%.

Analysis of Mexican Water Basins and Regions

For our analysis, we divided the country into 5 regions that group

states with similar characteristics like weather, population, and

aquifer resources with each region including two or more basins:

Hydro-Agriculture Infrastructure

The Mexican hydro-agricultural infrastructure has the following

characteristics. There are over 4000 dams in Mexico from which 667 are

classified as large dams according to the International Commission on

Large Dams (ICOLD). The storage capacity of dams in Mexico is 150

billion m3 with the 100 most important dams having a total capacity of

118 billion m3, representing 79% of the total storage capacity in the

country. Of these top 100 dams, 36 are used exclusively for

agricultural purposes while 44 are used for agricultural and other

purposes.

During 2008, the irrigated land represented 25% of the total national

agricultural land surface, while the other 75% was fed from seasonal

water sources. Nonetheless, the production value of irrigated

land represented over 60% of total production. Regarding the

total amount of water extracted from aquifers, 69% is used for

agricultural irrigation.

In Mexico, the infrastructure areas of irrigation represent 6.5 million

hectares making it the 6th most irrigated country in the world.

Of the surface with irrigation infrastructure, 54% corresponds to 85

Irrigation Districts (IDs) and 46% to the more than 39 thousand

Irrigation Units (IUs). The IDs and IUs - defined below - use almost

the same volume of water, with the Districts using 48.5% of the total

volume of water assigned for the agricultural sector, and the Units use

the 51.5%.

Water Irrigation Systems, Distribution and Productivity in Mexico

Irrigation Districts (IDs) - Of the 6.5 million hectares with

irrigation infrastructure, 3.5 million (54%) correspond to 85 IDs.

Those IDs are located in almost every state except for Campeche,

Tabasco, and the Federal District. Almost 75% of the ID areas is

concentrated in 6 states: Sinaloa, Sonora, Tamaulipas, Michoacan, Baja

California y Guanajuato – four northern states and two central states.

The IDs are established under Presidential Decree and they are formed

by one or more surfaces whose perimeters enclose an irrigation

area. Said area or ID has hydraulic infrastructure works,

superficial and underground water sources and storage which can but do

not have to include more than one or several IUs. Each ID must

have a concession title that is provided to users (farmers) organized

as a User Civil Association (ACU) by Conagua. This concession gives

these ACUs the possibility to use a certain amount of water during the

year and establishes the source of said water. The main crops in

IDs are grains (corn, wheat and sorghum), sugar cane, beans, and to a

lesser extent, horticulture products generally fed with underground

water from private wells.

Most of the IDs are supplied by superficial water which from storage

dams and water channels. Each water basin has a Basin Council which

determines the volume of water that will be assigned to users depending

of the current dam storage realities. On the other hand, IU main water

sources are subterranean (aquifers) generally obtained from wells as

well as small dams and other small water storage bodies. And only 1/3

of the water utilized for agriculture which includes agriculture,

aquaculture, livestock, and other related areas, comes from

subterranean sources.

Irrigation Units (IUs) – Of the 6.5 million hectares with irrigation

infrastructure, 3 million hectares (46%) correspond to the more than

39,000 IUs. These IUs are agricultural areas with water infrastructure

although different from an ID in that they are commonly operated by

small land owners and communal farmers and that they obviously have

smaller land surfaces and both less and lower technology than the

IDs. IUs can be integrated by ACUs or other entities organized to

provide irrigation services and operate hydraulic infrastructure works

for the reception, conduction, regulation, distribution and dispersion

of national water assigned to agricultural irrigation.

Water productivity in IDs and IUs is a key indicator to evaluate the

efficiency in the use of water for agriculture. Said productivity

includes the efficiency in driving the water from the source to the

field and its use directly in the fields which is where the majority of

the way, as much as 70%, is lost. In general, the

productivity of irrigated areas is 3.7 times higher than those fed with

seasonal water sources. Despite the fact that irrigated areas are

substantially less than those fed by seasonal sources, irrigated land

generates more than half of the national agricultural production.

Conagua reports that the average productivity in irrigated areas is

about 27.3 ton/hectare, significantly higher than in the seasonal

surface of 7.8 tons/hectare. However, according to contacts in

the industry, while they confirm this 4 to 1 difference in the

productivity, they indicate that said productivity per ton is probably

closer to half of the figures provided by Conagua.

IUs as well as IDs were established and designed according to

technology for the distribution of water by gravity systems. In many

cases, they only built channel networks and principal drainage systems

leaving the rest of the infrastructure works in the fields to the

users. This situation together with accumulated deterioration from

several decades of insufficient spending on preservation and

maintenance programs generated a backlong of essential rehabilitation

requirements that led to a dramatic drop in the efficiency of

agricultural and general Mexican water management.

Irrigation methods are rudimentary or traditional in more than 80% of

Mexican surface (superficial) irrigation and their efficiency in terms

of water use is very low, somewhere between 33 to 55%. With the use of

better techniques and irrigation infrastructure modernization,

the water use efficiency could increase to 50 to 65%, which would

notably lower the extraction of water from Mexican aquifers and allow

these water savings to be used in other applications like the better

preservation of rivers, lakes and aquifers.

The intensity in the use of land for agriculture is an important

characteristic to review when analyzing IDs and IUs. A great part of

the IDs are cultivated twice a year in the crop cycles autumn-winter

and spring-summer. Nonetheless, some districts are only harvested once

a year. In 92% of IUs, with their water source being superficial

waters often based on season water sources, only one harvest is

programmed due to the lack of water, further exacerbated by the

increase non-agricultural water demand, the regular uncertainty of

availability, and the drop in the pumping levels. Conagua

officials insist that this very high percentage can be reduced through

technical irrigation assistance programs for producers as well as the

substitution of crops with much lower water demands such as barley and

chickpea.

Conagua Budget for Hydro-Agricultural Infrastructure

In the last five years (2006-2010), the general Conagua budget was

increased almost 210%. Meanwhile, the budget for

hydro-agricultural infrastructure during this period was increased

almost 237% with double figure annual inceases demonstrating how

Conagua recognizes the importance and severe problems of water in the

agricultural sector. Below is the breakdown of the Conagua budget

during the last five years and the budget information for 2011:

| YEAR | TOTAL BUDGET (Billions of Pesos) |

ANNUAL INCREASE |

BUDGET FOR AGRICULTURE (Billions of Pesos) |

ANNUAL INCREASE |

| 2006 | 16.6 | 3.8 | ||

| 2007 | 19.5 | 18% | 4.8 | 26% |

| 2008 | 29 | 48% | 5.7 | 18% |

| 2009 | 32 | 10% | 8 | 40% |

| 2010 | 35 | 9% | 9 | 12% |

| 2011 | 36.4 | 4% | N/A | N/A |

The Mexican federal government has increased Conagua resources in recognition of the importance of water issues at all levels and in light of the increasing need for potable water treatment, wastewater treatment and water infrastructure. Regarding hydro-agricultural spending, said funding is designated to create and maintain water and wastewater infrastructure, to introduce new water technology and irrigation infrastructure improvements, and to better train users on the benefits of these technologies and improvements. In the next few years, the need for a more efficient agricultural system will be an even greater priority due to the increase of the population that requires both more food and more water, both of which they can obtain from a more efficient Mexican agricultural system.

In our next edition, we will expand one some of the above issues and discuss some other important hydro-agricultural issues in Mexico.

Mexico City, known officially as the Mexican Federal District (DF), is one of the largest cities on the planet with more than 10 million inhabitants although less than half of the size of the Valley of Mexico which includes another 10 million people. Due to these numbers, the major problem which it faces is rooted in the lack of public services and the water sector is no exception.

Continuous urban growth and a lack of local water sources and other

factors have negatively affected the water supply, and deliver and

drainage systems for the entity. The Federal District Water System

faces considerable challenges in its attempt to repair leaks and treat

waste water. In addition, if one bears in mind that 70% of the water

supply comes from the aquifer subsystem located underground the city,

one begins to understand the problem of the regular if not constant

floods provoked by the land sinkage product of the overexploitation of

the aquifer subsystem. This continuously uncontrolled water flows lead

to infrastructure damages especially to the potable water and

sewer/drainage networks. This together with the inadequate management

of municipal and industrial waste paints a worrisome picture for the DF

water system.

This article will present the current status of the DF water system in

relation to existing infrastructure and the future needs for future

potable water, potable water and sewer/drainage systems, and potable

water and waste water treatment plants.

Potable Water Situation in Mexico City

The Federal District Water System is responsible for the supply of

potable water and the storage and management of waste water in the DF

whereas Conagua, its federal counterpart, is entrusted to provide the

water in block to the DF to operate and maintain the great majority of

deep wells and to organize large and interstate and interbasin

hydraulic projects.

Despite the existence of 11,000 kms of distribution lines and more than 300 storage tanks with a capacity of more than 1.5 million cubic meters (m3), many DF inhabitants depend on non-water system sources lke tanker trucks or local wells and springs to obtain potable water. Likewise, approximately 40% of the southern part of the DF does not have access to sewer or potable water systems. Also, there exists the problem that the DF loses 50 % to 60 % of its potable water between its source and the end-user in the distribution system, As a result, there is a latent need for the construction of new distribution infrastructure and the repair of the existing system.

Before continuing our analysis of DF infrastructure, projects, and

budget issues, it is important to mention the vital role that the Lerma

– Cutzamala System plays for the DF. This system was constructed to

help avoid the overexploitation of the aquifer of the Valley of Mexico,

transporting waters from the Cutzamala River to the Federal District

via the Peripheral Aqueduct. The water imported is disinfected with

chlorine and then incorporated into th Lerma-Cutzamala aqueduct before

joining the DF potable water distribution system. The Lerma-Cutzamala

System possesses 7 dams, 6 macro pumping plants, almost 73 kms of open

channels, 44 kms of tunnels, 218 kms of aqueducts and the Los Berros

water treatment plant that, being the largest potable treatment plant

in Mexico, it provides 1.5 billion liters of water to Mexico City,

equivalent to 26% of the total DF water supply. Despite the incredible

size and dynamic of Lerma-Cutzamala, this infrastructure has turned out

to be insufficient to continue to meet the basic, total needs of the

DF. As a result, the DF and Conagua authorities continuing

working on new water source supplies to resolve this problem.

The DF potable water supply is shaped by external and internal sources

located in Mexico City/DF, the State of Mexico which surrounds the DF

and the State of Michoacán which neighbors the State of Mexico.

The external sources are superficial waters and represent 35% of the

total DF system. Internal sources consist of the local aquifer

which represents the other 63%, composed of the Lerma-Cutzamala and the

Mexico City aquifer.

The biggest problem that the DF distribution system faces is the loss

of potable water which can reach upwards of 60% of the total water in

the distribution system. This permits many DF zones to be without water

service or with intermittent service. The important DF

delegations or city subdivisions/boroughs of Álvaro

Obregón, Coyoacán and Cuajimalpa are the major but not

only delegations that feel the affect of these problems.

In a city where the population grows almost unabated and where the

geography is very irregular and thus impedes the delivery of water to

its inhabitants, the need to have an more efficient potable water

system and a reliable distribution system is clear. In addition, the

excessive DF aquifer extraction has forced DF and Conagua officials to

bring water into the DF from basins outside of the Valley of

Mexico. In light of the uniquely high and difficult DF terrain,

bringing in water from outside of the Valley of Mexico has provoked the

need for the construction of 227 pumping plants to get water to the 1.5

mile high city and then to provide water to its even higher areas.

The DF potable water distribution system is made up of a principal and

secondary network. The principal network has 690 kms of pipelines of

between .5 and 1.7 meters in diameter. The secondary network has more

than 10,000 kms of pipelines of .5 meters in diameter along with 243

storage tanks with a 1.5 million cm2 capacity. The DF Water System's 27

treatment plants and 377 chlorination stations supply close to 35,000

liters of potable water per second but this only meets 90% of the

potable water requirements of its inhabitants. The DF potable water

supply has always been problematic but this has been accentuated in

recent years but some extreme drought conditions. As a result, the DF

invested only a modest sum, 1 billion pesos ($ 83.3 million USD) in

2009, to begin the rehabilitation of potable water

lines.

For the improvement of the potable water supply, the DF has a total

budget through 2012 of 4.47 billion pesos ($373 million USD).

From these funds, Wisconsin's Trade Office in Mexico expects more

related works during 2011 and 2012. It is important to mention that

these funds are strictly DF funds and additional Conagua funds for

these projects will make total available money more than double the

above mentioned amounts. While DF potable water projects will

move forward in 2011, it is important to mention that an even greater

ongoing priority is in the rehabilitation of the DF deep drainage

system.

Deep Drainage System Situation in Mexico City

The DF system for carrying waste water out of the Valley of Mexico

consists of three areas: (a) the above-ground Great Canal, (b)

complementary river systems (principally the Hondo River, the

Churubusco River, and the De la Piedad River) and (c) the subterranean

Deep Drainage System. The DF Deep Drainage System was constructed

in 1967 and put in operation in 1975. It is made up of a 6.5

meter in diameter tunnel designed originally to remove waste water and

rain.

Originally, it was designed to work exclusively during the rainy season

and that during the low water season, it could be closed for

inspection, cleaning and maintenance. However, due to some

regional collapses in lands affected by these structures, it has not

been possible to inspect these tunnels as had been hoped. And,

last year, when the tunnel was temporarily closed for some partial

inspections during the dry season, an unexpected heavy rain occurred

and severe flooding occurred in the eastern part of the city.

In general and as a result of this very controversial flooding

incident, the attention of the water sector has refocused extensively

on the rehabilitation of the DF deep drainage tunnels. As a

result, DF investment on potable water infrastructure decreased last

year by more than 50% vs 2009 totals, with said funds being transferred

to Deep Drainage System projects.

This system includes a Central Issuer Channel, 9 interceptors with a

length of 154 kms. Below is a table that shows general

information about this system.

| DF Deep Drainage System | Length (Km.) | Diameter (m) | Capacity (m3/s) |

| Central Emission Tunnel |

50.0 |

6.5 | 220 |

| Central Interceptor |

16.1 |

5.0 |

90 |

| Interceptor Center-Center |

3.7 |

5.0 |

90 |

| Interceptor East |

22.2 |

5.0 |

85 |

| Interceptor Center - East |

16.0 |

4.0 |

40 |

| Interceptor - West |

16.5 | 4.0 |

25 |

| Interceptor Iztapalapa | 5.5 | 3.1 | 20 |

Waste Water Situation in Mexico City

Another one of the serious problems that the DF Water System has to

face is the lack of waste water treatment and treatment capacity.

Currently, there are 25 waste water treatment plants in the DF with an

installed capacity of 6,640 lps. However, the capacity of these plants,

2,500 lps, represents only 38% of the capacity that would be needed to

treat total DF waste water volumes. With this limited capacity and with

the vision of treating DF waste water in Atotonilco, outside of the

Valley of Mexico, it is not all that surprising that only 7% of DF

waste waters are currently treated.

There are 6 waste water treatment plants in northern Mexico City with a

combined installed capacity of 700 lps. In the central area, there are

5 plants whose combined installed capacity is nearly 5 000 lps, with

the “Cerro de la Estrella” plant being the largest of these plants with

80% of the total capacity in the central area. Finally, in the southern

area, there are 5 plants with a combined installed capacity of 800

lps. It is important to mention that 5 billion pesos ($416.6

million USD) is currently programmed for the installation of new

technology and to increase the production of treated waste water from

2.5 m3/s to 7.2 m3/s by 2012. In the future, the DF hopes that

this water treatment will result in important, additional water reuses

which will alleviate some DF aquifer concerns and eventually recharge

aquifers.

Another challenge has to do with the storage of waste water prior to

its treatment or delivery outside of the Valley of Mexico. Most

waste water storage areas are located in the northern part of the city

where all DF waste water is directed on their way out of the Valley of

Mexico. However, this leads to an uneven, less than ideal distribution

of waste water storage. To address this the DF has launched

projects to add other reserve basins especially in the Iztapalapa area

in the southern part of the city.

With recent flooding problems, the DF budget priority has been somewhat

away from treatment plants and towards the rehabilitation of deep

drainage system tunnels. However, the DF has made the

rehabilitation of its existing waste water treatment plants, such as

the “Milpa Alta” in southern part of the city, a priority as

well. On the potable water side, an important project is the

construction of a potable water treatment plant in “Cerro de la

Estrella”, in the south area of the city, which seeks to build an

infiltration pond and to return this treated water to the aquifer – the

first effort of its kind in Mexico. In addition, the DF has sought to

invest in wetlands construction and similar “swamps” for waste water

maintenance, especially in the water abundant areas of Xochimilco and

Tlahuac in the southern part of the city which they hope will also help

in with water level issues in these wetland areas.

Conclusion

With the above information on DF potable water, waste water, and water

treatment issues, we can get a glimpse of the DF water system and

infrastructure challenges. These problems must be attacked on all

fronts as they are circular problems. The exploitation of the DF

aquifer for drinking water makes Mexico City land continue to sink, in

some areas as much as 30 cm per year. With the fall in ground

water levels, it is necessary to pump deeper producing lower quality

water creating further land degradation which increases operation,

maintenance and water purification costs. In addition, the supply and

drainage network are affected as land subsidence creates more pressure

and leads to cracks and fissures that causes 50-60% potable water loss.

When you combine these problems with the lack of wastewater treatment

and a growing population, one can visualize the seriousness of the

challenge that the DF Water System faces – and the level of assistance

that they are likely to require from domestic and foreign companies to

help solve these problems.

The DF and Conagua have increased their budgets for DF water projects

during the last few years with Conagua funding of DF water projects as

its top priority, doubling funding from just over 5 billion pesos in

2009 to over 10 million pesos (over $800 million USD) in 2010.

This increase made the DF Conagua budget three times that of the State

of Mexico and larger than the budgeted funds for the next give most

important Mexican states. Still, these funds are clearly not enough to

solve these problems in general and because too many important DF

projects have had to be put off to address other more urgent and

politically sensitive water issues.

In response to these realities, there have been some initial proposals

to increase private sector participation in new infrastructure projects

and rehabilitation and maintenance programs. Although these measures

are still in planning stages, many water officials believe that this is

the only way to address the problems of water sector in the DF. These

types of programs will create more business opportunities for domestic

companies and for foreign companies to provide products and

technologies for better funded and therefore more generally stable

integrated projects and solutions.